The upcoming DNR timber sale known as “Little Lilly” is set to be auctioned for clearcut logging on October 30th, 2024. It is a four-unit, 89.2 acre sale that straddles the Van Zandt Dike, with the majority of the sale located within the Middle Fork Nooksack watershed.

Members of our Whatcom Forest Watch coalition visited the forest and observed Little Lilly for themselves. We have identified this proposed timber sale as being largely made up of mature, naturally regenerated forest. Structurally complex, biodiverse and mature forests play a critical role in mitigating climate change through carbon sequestration. They are also more resilient to wildfires. These forests regulate water flow and quality by capturing precipitation, reducing soil erosion, slowly releasing water into streams during dry periods, and filtering pollutants (such as those created through industrial logging) before water reaches streams and groundwater.

Mature forests have well-established mechanisms for natural regeneration and resilience to disturbances, including seed banks in the soil, canopy gaps that allow light for understory regeneration, and adaptations that enable species to recover after natural events like storms or fires. Razing diverse, mature forests and turning the land into into one- or two-species tree plantations disrupts the critical ecological roles that they serve locally and globally. And our communities risk losing the water filtration, flood regulation, summer water supply, and climate benefits these forests give us for free.

While Unit 1, which makes up less than 3 acres (2.92) of the 89.2 acre sale, has an estimated stand age of 64-74 years old, the remainder of the sale largely consists of mature forest. The estimated stand origin dates of Units 2 and 3 range from 1915 to 1935. Unit 4, which contains the most mature forest in the sale, is a 49.9 acre unit and has an estimated stand origin date range of 1858 to 1865 (159-166 years old). DNR’s policy on old growth maintains that stands 5 acres and larger that are in the most structurally complex stage of stand development and originated naturally before the year 1850 are classified as old growth and off limits to logging. If this forest were just 9 years older, it would likely be designated old growth.

Unit 4 contains dozens of old-growth trees and snags, adding to the intrinsic value and distinctiveness of the sale. While these trees that we observed in our survey were marked to not be cut or traded, it is still within the DNR’s policy to permit felling of these trees if they are deemed an “operational hindrance.” This policy poses a significant problem because it allows the felling of ecologically valuable trees that contribute to the forest’s biodiversity and structural complexity. Old-growth trees and snags provide critical habitat for various species, including potential nesting habitat for marbled murrelets, and support essential ecosystem functions such as nutrient cycling and carbon storage. Given the alarming rate at which mature and old forests are being converted into single-species plantations, preserving these remaining trees is crucial for maintaining the ecological continuity and health of the entire region.

Stands of large, mature trees are worth more alive than cut down

In conifer forests of Western Washington, individual large diameter, structurally unique trees are important habitat. These trees are characterized by very large diameters (60 to 90 inches or more, depending on the species, according to the Habitat Conservation Plan) and possess large, strong limbs; open crowns; large, hollow trunks; broken tops and limbs; and deeply furrowed bark.

During our survey of Unit 4, we found many Douglas fir trees that were 60 inches in diameter and larger — many of which had faded labels or none at all (DNR marks certain trees that should be left uncut). DNR’s own Old Growth Assessment for Unit 4 of Little Lilly states on page 9 that there are Douglas fir trees up to 45 inches in diameter in the area where we documented trees over 60 inches wide.

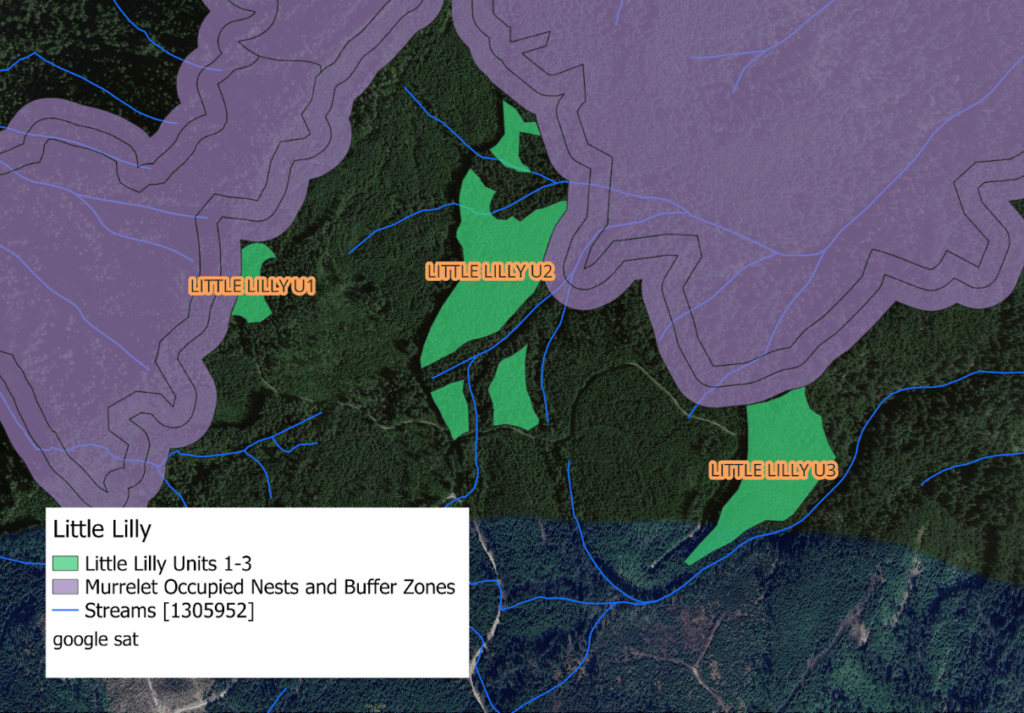

Units 1, 2, and 3 of Little Lilly border the buffer zones of known occupied marbled murrelet nesting sites. While murrelet populations have seen an increase in Oregon and California, this protected species continues to decline in Washington by 4-5% annually, (Lance & Pearson, 2020), with habitat loss and fragmentation considered the main contributors to their decline (Desimone 2016, US FWS, 1997).

The marbled murrelet relies on mature and old-growth forests for nesting, typically selecting large, moss-covered branches high in the canopy. These specific habitat requirements make the preservation and expansion of suitable forest areas crucial. By allowing the adjacent mature forest in Unit 2 to continue its natural progression towards old-growth, the DNR would be supporting the creation of future nesting habitat. This is essential for the DNR to fulfill their obligations and reverse the current decline in murrelet populations in Washington.

Mature forests like Little Lilly are vital for salmon and reducing flood, landslide, and drought impacts

The majority of Little Lilly sits steeply above the Middle Fork Nooksack River.

Long-term ecological research conducted in the Pacific Northwest shows that industrially logged tree plantations can reduce summer streamflows —right when humans and wildlife need water the most — in smaller basins by as much as 50% compared to watersheds with mature forests (Segura et al. 2020; Perry & Jones 2017). These reductions in streamflows persist for more than 50 years, which means that clearcuts in our watersheds today could contribute to water shortages well into the latter half of this century. Research also shows that when conducted at watershed-scale, clearcut logging and road building can contribute to significant increases in peak flows (Grant et al. 2008). That means higher flood risks. Higher peak flows also lead to higher turbidity levels (i.e., lots of sediment gets stirred up into the water) and harms habitat features that fish rely on (Nooksack Indian Tribe 2017; Tschaplinski & Pike 2016).

It’s time to decouple school funding from destructive clearcutting

Some of the proceeds from the timber sale auction are set to go to the state’s Common School Fund. It is important to point out that this fund makes up less than 1.4% of total school construction funding according to Washington’s Superintendent of Public Instruction Chris Reykdal, who is also on the Board of Natural Resources (BNR). Reykdal has argued for the benefits of leaving mature forests standing since they only make up about 5% of DNR lands, and at recent BNR meetings has voted against approving any sale containing mature forest. At the July 2024 BNR meeting, Reykdal proposed to fellow board members that all mature forests could be protected immediately for only around $8 million per year from the legislature. This could easily be funded through the Climate Commitment Act’s “Natural Climate Solutions” account, which is specifically designed to increase Washington’s much-needed climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Join us in calling on the DNR and BNR to oppose this clearcutting proposal!

Many thanks to the field check volunteers with the Whatcom Forest Watch work group and our colleagues at Center for Responsible Forestry for helping lead this effort!