For background on what the Nooksack water rights adjudication process is and why it’s necessary, read Part 1.

The Nooksack adjudication is only the second time the Washington State has adjudicated an entire watershed. The first was in Washington’s most productive agricultural basin: the Yakima River basin.

How we can learn from (and improve upon) Washington’s first-ever adjudication in Yakima

The Yakima River adjudication yielded a wide variety of benefits. Thankfully, because of how much the adjudication managers learned from that lengthy 42-year process, the Department of Ecology expects the Nooksack adjudication to take 10-15 years to complete. While that may still sound like a lot of time, remember that thousands of water users’ water rights and actual water usage are being taken into account individually.

A key outcome in Yakima was the Yakama Nation’s water rights, both on- and off-reservation, were quantified for the first time. Because treaties between the US and sovereign tribal nations are the supreme law of the land, allocating tribes’ water (and fishing rights made possible by that water) is vital.

Another major benefit was the development of the 2012 Yakima Basin Integrated Plan (YBIP). The YBIP is an unprecedented, collaborative planning effort that gives farmers and fishery managers security and certainty in how much water they can access. This comprehensive and ambitious plan includes programs to restore fish habitat, improve fish passage, enhance water quality, increase water quantity, and improve water use efficiency. One major component of the YBIP is to raise the height of dams and reservoirs, allowing more water to be stored and gradually released for fish and farmers downstream. Hundreds of millions of dollars from the state and federal government are being leveraged to advance this plan’s comprehensive goals, none of which would have happened without adjudication spurring governments and stakeholders to explore collaborative solutions.

Yakima’s plan used forests to make everyone’s slice of the water “pie” bigger

The YBIP led to the acquisition of over 50,000 acres of private forestland in the upper Yakima watershed to create Washington’s first state-owned community forest. In the hotter, drier climate of the 21st century, the natural water storage benefits provided by forests are crucial to protecting fisheries and farms. The Teanaway Community Forest was formed to improve habitat conditions in the Teanaway River basin and boost the watershed functions that healthy forests provide, like slowly releasing water in the summer. Owned by Washington DNR and co-managed with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW), the community forest remains a working forest that balances a wide variety of benefits, such as improved fish habitat, expanded recreational opportunities, sustainable timber production, and more. DNR and WDFW are required to consult with the Teanaway Community Forest Advisory Committee, which includes representatives from state, local, and tribal governments, as well as stakeholders with conservation and agriculture backgrounds.

The Yakima basin provides a template for how adjudication can spur collaborative solutions to increase the size of the pie for all (“the pie” being the total amount of water available in late summer). The Nooksack watershed is very different being on the west side of the Cascades. Solutions for our watershed must be calibrated to the geography, hydrology, economy, and politics of this place. But we can still learn from the landscape-level approach taken by folks in the Yakima basin and avoid piecemeal, less effective solutions.

What solutions can we advance here in Whatcom County that accomplish multiple (and seemingly opposing) objectives? We must embrace a vision for the future that includes:

- Healthy rivers and streams teeming with strong populations of salmon and steelhead; Tribal treaty rights to fishing and water rights to are upheld

- A robust agriculture economy that benefits our communities in perpetuity

- Diverse ecosystems that support a wide range of plant and animal species

- Thriving communities that are resilient to extreme winter floods and extreme summer droughts as the climate gets hotter.

There are now costly proposals to install major dams on the forks of the Nooksack River, which proponents justify with the summer and winter extremes we’re already experiencing due to climate change. There are others who propose dredging out sediment from the Nooksack and building higher levies along its banks to mitigate flood risks, but these are short term band-aids that seek to maintain the status quo and ignore the reality of how rivers move sediment. Simply put, achieving true watershed recovery will require innovation and collaboration unlike we’ve seen in our county — we won’t get far if we just follow the last century’s playbook.

Instead, we must restore the kinds of natural infrastructure that have shaped our rivers and streams for millennia. Promoting natural solutions to watershed recovery doesn’t only help fish, wildlife, and ecosystems recover. It’s also more economically sustainable, equitable and durable in the long run. Healthy forests, wetlands and riparian areas (land adjacent to streams) are excellent at storing and gradually releasing water in the late summer. They’ve done it for eons, and they do it for free.

What Nooksack water solutions should we prioritize?

1. Restore floodplains

For millennia, the Nooksack watershed relied on winter floods that inundated broad swaths of floodplains, wetlands, ponds, lakes, and riparian forests. These floodwaters percolated into the ground to fill the underground reservoirs we call aquifers. Unfortunately, over a century of aggressive logging and farming practices have severed the river from its historic floodplain, confining the river to an unnaturally straight and narrow channel. Since these aquifers are the river’s primary source of water in late summer, diminishing aquifer recharge has led to lower and lower summer streamflows.

We can restore floodplains by removing rip rap (big rocks used to stabilize river banks) and setting levies back, giving the river some elbow room to operate naturally. Establishing a healthy river corridor allows a river to meander and form the kinds of habitat that salmon and other critters need to thrive. This approach also mitigates flood risks because it designates a clear pathway for floods to take and ensures that water doesn’t pass over the set-back levies that are maintained. It would also help rebuild the groundwater supply many rely on.

2. Bring back the wood!

When European settlers came to this area 150 years ago, they found rivers and streams chock full of wood. One log jam near present-day Ferndale stretched several miles before it was removed in the late 1800s. With the removal of log jams, the braided Nooksack River began to unravel to become a more single-channel river like it is today. Scientists now understand that wood in waterways is essential to create pools, side channels, and other habitat features that salmon depend on as juveniles and adults. Today, both Lummi Nation and the Nooksack Indian Tribe are leading the effort to bring wood back into rivers.

Over the past 25 years, the tribes and partner agencies have installed hundreds of engineered log jams on the Nooksack River and its major tributaries. The results are clear: log jams are fish magnets! Many believe that if the tribes and partner agencies are able to scale up these projects, the river will continue to restore its historic shape and function to the benefit of all. Slowing the river’s flow with log jams allows more water to percolate underground as well, feeding the river in drier months.

Another major focus of watershed restoration has been to plant trees along rivers, streams, and wetlands in an effort to shade waterways, keeping them cooler and more suitable to salmon habitat. Riparian forests serve as an input for woody debris, which naturally form log jams that fish depend on. These forest ecosystems also provide habitat for a wide range of species, including the bugs that juvenile salmon eat as they rear in freshwater.

3. Protect mature forests, restore dense plantations, and plant riparian forests

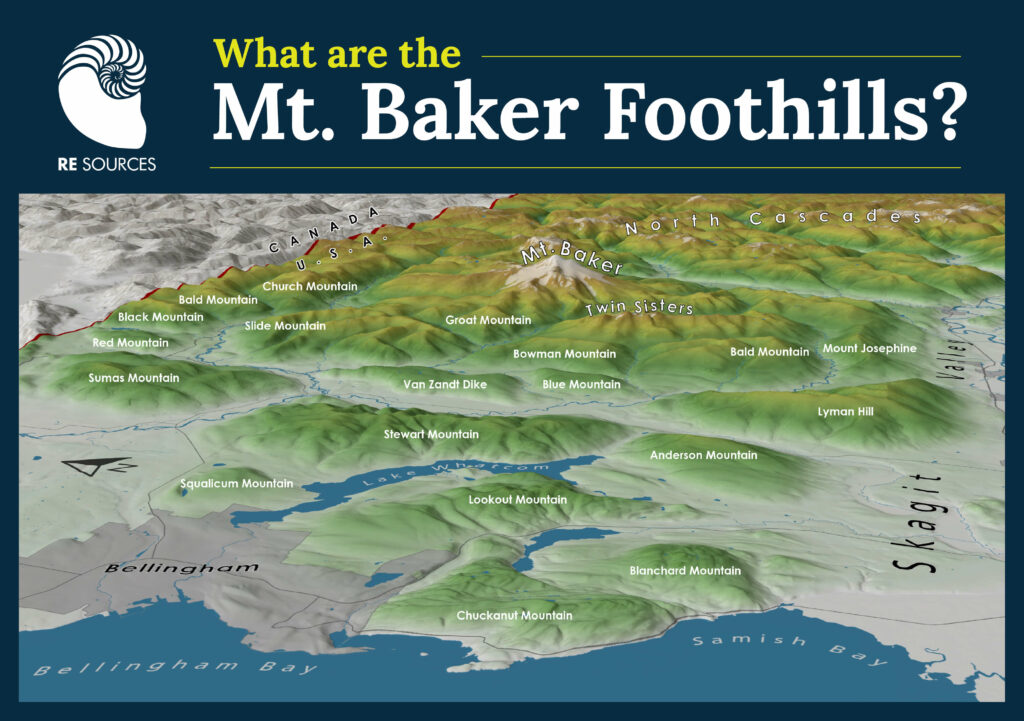

Forests used to cover almost 100% of the Nooksack watershed. That means the hydrology of this river is characterized by how our forests are managed. Large swaths of land were deforested to make way for cities and farms, and others were logged and replaced with dense tree plantations, which don’t help feed rivers with slowly released water like intact forest ecosystems do. The science has become increasingly clear that to restore the health and resilience of our watershed, we must protect the mature and old-growth forests that remain, while restoring complexity and diversity in the monoculture tree plantations that blanket most of the Mt Baker Foothills.

This approach is known as “ecological forestry,” and it’s gaining momentum throughout the Pacific Northwest. As ecological foresters like to say, “forest” is not the plural of “tree” — a forest is so much more. To learn about how ecological forestry can improve the resilience of our watersheds to climate change, check out our videos on the topic:

The Future of Forests with Dr. Jerry Franklin

There are other important solutions to consider, such as water banking, irrigation efficiency, and thoughtful water storage infrastructure; but we’ll get the biggest bang for our buck by adopting watershed-scale solutions that work with natural systems instead of against them.

To learn more about our work, visit our Forests and Watersheds program page, and sign up for our emails to receive timely updates and actions you can take to make sure your voice is heard while state and local officials navigate the adjudication process.